"I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day in January of 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of 1974."

"But now, at the age of forty-one, I feel another birth coming on. After decades of neglect, I find myself thinking about departed great aunts and -uncles, long-lost grandfathers, unknown fifth cousins, or, in the case of an inbred family like mine, all those things in one."

"Three months before I was born, in the aftermath of one of our elaborate Sunday dinners, my grandmother Desdemona Stephanides ordered my brother to get her silkworm box."

"Up until now Desdemona had had a perfect record: twenty-three correct guesses."

"She didn't want a boy. She had one already. In fact, she was so certain I was going to be a girl that she'd picked out only one name for me: Calliope."

". But when my grandmother shouted in Greek, "A boy!" the cry went around the room, and out into the hall, and across the hall into the living room where the men were arguing politics."

"Forbidden Fruit" - from the letters of Abelard and Heloise

0 comentários Publicada por Midnight snacks"You alone have the power to make me sad, to bring me happiness or confort"

"Home and wealth may come down from ancestors; but an intelligent wife is a gift from the Lord"

"In my case, the pleasures of lovers which we shared have been to sweet - they cannot displease me, and can scarcely shift from my memory. Wherever I turn they are always there before my eyes, bringing with them awakened longings and fantasies which will not even let me sleep"

"(...) virtue belongs not to the body but to the soul"

Peter Abelard (1079-1142) was a French philosopher, considered one of the greatest thinkers of the 12th century. Among his works is "Sic et Non," a list of 158 philosophical and theological questions. His teachings were controversial, and he was repeatedly charged with heresy. Even with the controversy that surrounded him at times, nothing probably prepared him for the consequences of his love affair with Heloise, a relationship destined to change his life in dramatic ways.

Heloise (1101-1164) was the niece and pride of Canon Fulbert. She was well-educated by her uncle in Paris. Abelard later writes in his Historica Calamitatum: "Her uncle's love for her was equaled only by his desire that she should have the best education which he could possibly procure for her. Of no mean beauty, she stood out above all by reason of her abundant knowledge of letters."

She was supposedly a great beauty, one of the most well-educated women of her time; so, perhaps it's not surprising that Abelard and she became lovers. Also, she was more than 20 years younger than Abelard... And, of course, Fulbert discovered their love.

They were separated, but that didn't end the affair...

"Of Mistresses, Tigresses and other Conquests" - Giacomo Casanova

0 comentários Publicada por Midnight snacks

"As true virtues are merely habits, I dare say that the truly virtuos are those fortunate people who practice virtue without any effort at all"

"Death is a monster that chases the rapt spectator from the theater before the play he is watching with infinite interest has ended. This alone is reason enough to despise it"

"The happiest man is he who best understands the art of finding happiness without letting it encroach upon is duties; and the an happiest is he who has chosen a way of life in which he finds himself with the sad obligation to plan every day, from morning till night"

"Nothing is more precious to the thinking man than life itself; yet in spite of this, the greatest voluptuary is he who best practices the difficult art of making it pass quickly"

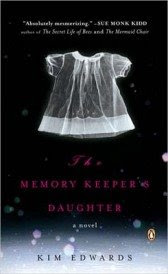

“For the next few hours, they read and talked. Sometimes she caught his hand and put it on her belly to feel the baby move. From time to time he got up to feed the fire, glancing out the window to see three inches on the ground, the five or six.”

“The stairs creaked with his weight. He paused by the nursery door, studying the shadowy shapes of the crib and the changing table, the stuffed animals arranged on shelves. The walls were painted a pale sea green. His wife had made the Mother Goose quilt that hung on the far wall, sewing with tiny stitches, tearing entire panels if she noted the slightest imperfection.”

“ On an impulse he went into the room and stood before the window, pushing aside the sheer curtain to watch the snow (…) He stood there for a long time, until he heard her moving quietly. He found her sitting on the edge of the bed, her head bent, her hands gripping the mattress.

“ I think this is labor”, she said, looking up. Her hair was loose, a strand caught on her lip. He brushed it back behind her ear. She shook her head as he sat beside her. “I don’t know. I feel strange. This crampy feeling, it comes and goes.”

“When they reached the car she touched his arm and gestured to the house, veiled with snow and glowing like a lantern in the darkness of the street.

“When we come back we’ll have our baby with us”, she said. “Our world will never be the same.”

“They had been discussing names for months and had reached no decisions. “For a girl, Phoebe. And for a boy, Paul, after my great-uncle. Did I tell you this?” she asked. “I meant to tell you I’d decided.”

“Those are good names,” the nurse said, soothing.

“Phoebe and Paul,” the doctor repeated, but he was concentrating on the contraction now rising in his wife’s flesh.”

“It was a boy, red faced and dark-haired, his eyes alert, suspicious of the lights and the cold bright slap of air. The doctor tied the umbilical cord and cut it. My son, he allowed himself to think. My son.

“He’s beautiful,” the nurse said.

“It’s a boy”, the doctor said, smiling down at her. “We have a son. You’ll see him as soon as he’s clean.

He’s absolutely perfect.”

“Nurse?” the doctor said, “I need you here. Right now.”

“He saw her surprise and the her quick nod of comprehension as she complied. His hand was on his wife’s knee; he felt the tension ease form her muscles as the gas worked.”

“The doctor, who had allowed himself to relax after the boy was born, felt shaky now, and he did not trust himself to do more than nod. (…)

This baby was smaller and came easily, sliding so quickly into his gloved hands that he leaned forward, using his chest to make sure it did not fall. “It’s a girl,” he said, and cradled her like a football, face down, tapping her back until she cried out. Then he turned her over to see her face.”

“ Creamy white vernix whorled in her delicate skin, and she was slippery with amniotic fluid and traces of blood. The blue eyes were cloudy, the hair jet black, but he barely noticed all of this. What he was looking at were the unmistakable features, the eyes turned up as if with laughter, the epicanthal fold across their lids, the flattened nose.

A classic case, he remembered his professor saying as they examined a similar child, years ago. A mongoliod. Do you know what that means? And the doctor, dutiful, had recited the symptoms he’d memorized from the text: flaccid muscle tone, delayed growth and mental development, possible heart complications, early death.”

“The nurse stood beside him and studied the baby. “I’m sorry doctor”, she said.”

“ He thought of his wife standing on the sidewalk before their brightly veiled home, saying, Our world will never be the same.”

“There’s a place,” he said, writing the name and address on the back of an envelope. “I’d like you to take her there. I’ll issue the birth certificate, and I’ll call to say your coming.”

“Don’t you see?” he asked, his voice soft. “This poor child will most likely have a serious heart defect. A fatal one. I’m trying to spare us all a terrible grief”

“Is everything all right?” she asked. “Darling? What is it?”

“We had twins,” he told her slowly, thinking of the shocks of dark hair, the slippery bodies moving in his hand. Tears rose in his eyes. “One of each. I am so sorry. Our little daughter died as she was born.”

“ Caroline (the nurse) stared at the empty doorway. She felt in her pocket for her keys, the picked up the box with Phoebe in it. Quickly, before she could think about what she was doing, she went into the spartan hallway and through the double doors, the rush of cold air from the world outside as astonishing as being born. She settled Phoebe in the car and pulled away. No one tried to stop her; no one paid any attention at all. Still, Caroline drove fast once she reached the interstate.”

“ - Um dia destes dou à praia aqui, devorado pelos peixes como uma baleia morta – disse-me ele na rua da clínica olhando os prédios desbotados e tristes de Campolide”

“ Sentado nos teus ombros quase tocava os ramos dos castanheiros com a cabeça, aureolado de luz à maneira dos santos dos milagres, enquanto uma eternidade de fotografia me imobilizava o sorriso que encontro, tantos anos depois, no espelho do quarto, a troçar-me numa careta azeda.”

“ Percebia-se o ruído das máquinas de escrever do escritório, gente debruçada para as mesas, o desodorizante da secretária transformando o espaço livre, salas, paredes, corredores, num enorme sovaco depilado e morno: Já a comeste, velho?”

“ Um odor leve e adocicado evaporava-se das gavetas porque a tua água-de-colónia impregna tudo, até a ausência de ti quando te lembro.”

“ Uma ou duas vezes por semana, não sabia ao certo, procurava o psiquiatra para longos conciliábulos sibilinos. Vi-o uma ocasião: um tipo insignificante, amaricado, míope, de pasta no braço e sobretudo gasto: de que lhe falaria ela? Da infância nos Olivais, dos primeiros amores na Faculdade, bruscos e canhestros, da minha pessoa? E o que poderia aquele pateta marreco entender de mim? Pensa Se calhar traz na pasta o processo dela, o meu, desiludida história difícil e sem história da nossa relação.”

“ – Outro cigarro ? – diz a Marília, surpreendida – repara-me só na cor dos teus dedos.

O médico indiano exibe contra a janela uma radiografia do tórax:

- Cancro do pulmão – diagnostica ele – espino-celular aposto. Mais uns tempinhos a definhar e adeus minhas encomenda. Nessa altura o quarto da sua mãe já vai estar desinfectado e a cama vazia: pronta para si.”

“Os pássaros, explicava o pai encostado ao muro do poço da quinta, morrem muito devagar, sem motivo, sem se dar por isso, e um belo dia acordam de barriga para cima, de boca aberta, flutuando no vento.”

“Os campos sonâmbulos do Outono desdobravam-se, sem majestade, em pobres colinas redondas como crânios calvos: a Rua Azedo Gneco afastava-se deles com os seus livros, os seus retratos, os cartazes pregados na parede, o autoclismo eternamente avariado.”

“Pensa: Nunca me apetece voltar depois das aulas para casa, subir as escadas, meter a chave à porta, surges na moldura da cozinha a remexer qualquer coisa num tacho, Olá amor, eis os móveis do costume, os objectos do costume, a televisão acesa sem som e um tipo qualquer com olhos de robalo a perorar em silêncio lá dentro, Vou-me embora, adeus, ou fico , qual é a alternativa, ir para onde, serei mais feliz sozinho”

“Explica-me os pássaros. Assim, sem mais nada, explica-me os pássaros, um pedido embaraçoso para um homem de negócios. Mas tu sorriste e disseste-me que os ossos deles eram feitos de espuma de praia, que se alimentavam das migalhas do vento e que quando morriam flutuavam de costas no ar, de olhos fechados como as velhas na comunhão.”

“Em frente do prédio dele um grupo de garotos jogava a bola no alcatrão. Uma velha com um cão obeso e um livro de missa entrou na pastelaria vizinha para a torrada eucarística.”

“ Catano as vezes que escrevi o teu nome, com o indicador, nas janelas do Inverno, enquanto as letras escorriam para os caixilhos como se chorassem, lentamente pernaltas de uma espécie de lágrimas”

“Domingo era a chatice da desocupação, o quarto dos brinquedos resolvidos, o corpo a arrastar-se, maçado, pelos cantos. A mãe jogava as cartas com as amigas, na sala, num cintilação de pulseiras e de brincos, as bocas pintadas conversavam, como periquitos, de filhos, de criadas, dos empregos dos maridos.”

“O pai desliga sem responder, e eu fico com o telefone mudo encostado no ouvido, imóvel como uma concha sem mar. A voz aborrecida da rapariga do PBX pergunta:

- Pediu alguma chamada?”

“- Como é que se sente ? – perguntou numa voz derrotada, enquanto observava a mãe a pensar As lágrimas estão já do outro lado dos teus olhos, deslizam por dentro da cabeça, para a garganta, num ardor ácido de bagaço.”

“ – A única coisa que há para discutir – disse a Tucha – é a mesada das crianças, mais nada. Tenho ali uma proposta do meu advogado, vou-ta mostrar.

- Os pássaros – disse a Marília – que sabiam vocês dos pássaros?”

“Ao longo do corredor as paredes fitavam-no com ódio: Vais-te embora.”

“A mãe sorriu inesperadamente: a infância escorregou-lhe, lenta ao longo da boca, como a água num desnível de tábuas:

- Não te preocupes – disse ela – tratam tão bem de mim aqui.”

“Quando havia parentes o meu pai desdobrava o écran de tripé ao fundo da sala, montava o projector, apagava as luzes, um rectângulo branco surgia a tremer na tela, traços e cruzes vermelhas vibravam e dissolviam-se, um cone de luz onde o fumo dos cigarros se enrolava em volutas lentas sobre as nossas cabeças, e nisto o mar repleto de albatrozes, a forma afuselada dos corpos, os bicos pálidos abertos, os espanadores achatados das asas, dezenas, centenas, milhares de pássaros.”

“ – Prefere Letras – revelou a mãe – confessou-me a semana passada que queria estudar História. Fiquei banzada.

O pai deu um murro no bar Arte Nova, as garrafas e os copos saltaram:

- Letras? História? – (falava devagarinho numa surpresa imensa.) – Tens mesmo a certeza que esse parvo é meu filho?”

“Pensou fumar um cigarro, ler um livro, mas preferiu sentar-se no colchão para ver a manhã avançar palmo a palmo no sobrado, revelar os defeitos da madeira, as franjas do tapete, as pernas em arco, lascadas, dos móveis: o dia começa sempre por este desconforto físico, este estranho nascimento das coisas conhecidas, a tua cara desformada que dorme.”

“Os pássaros quando morrem – explicou o pai – flutuam de barriga para o ar no vento”

“Nunca me deixaste sequer revoltar-me, ir até ao fim das minhas zangas: a tua sombra enorme, tutelar e autoritária castrantemente protegia-me, e foi a partir daí que decidi ir para Letras.”

“ – Mal se lhe percebia o corpo – esclareceu o Carlos – comido pelos pássaros, pelo lodo da ria, pelo tempo que demoraram a encontrá-lo”

“Falava devagar, sem indignação nem zanga, mas eu cessara por completo de a escutar: achava-me ao colo do pai, sob o castanheiro do poço, numa tarde antiga que se não sumira nunca dentro dele a ouvir a explicação dos pássaros.”

“A sexta-feira instala-se, pensou ele a abrir o duche na casa de banho minúscula, e a observar o jorro que descia do tecto à laia de um cacho de filamentos de vidro que se abriam, se esmagavam no esmalte da banheira, se dirigiam para o ralo numa lentidão preguiçosa, e embaciavam a pouco e pouco o espelho, pensando Aposto que estendes agora a mão, às cegas, para a mesinha de cabeceira, à procura das pastilhas elásticas de morango.”

“Palavra de honra que a família acabou, palavra de honra que a Lapa acabou, nunca mais entramos sequer o portão daquela casa, e na claridade imprecisa de Lisboa, na claridade nevoenta de Aveiro, os teus olhos afiguraram-se-me tão tragicamente ocos de expressão como as órbitas de gesso dos defuntos.”

“Anunciaste Não quero filhos e tu sabias que eu sabia que o dizias por mim, pelo meu estúpido pavor do neto de um guarda-republicano de palito na boca, porque não conseguia despir-me do meu pai, da minha mãe, da terrina da Companhia das Índias em que me embalaram.”

“Na sala havia um álbum cheio de desenhos de homens nus com asas, de falcões com tronco de gente, de esquisitas misturas, como centauros, de pessoas e de pássaros: E se a mãe se levantasse agora de mesa, pensa, e começasse a voar, como um periquito aflito, sobre os pratos da sopa?”

“ – Vamos furar-lhes a barriga? – propôs o pai num riso cúmplice, a estender a manga para a faca de prata dos livros. – Se lhes rasgarmos a pança e virmos o que têm dentro, talvez consigas encontrar, percebes, essa célebre explicação dos pássaros.”

“ – Pronto – disse o pai segurando no insecto imóvel com as pontas dos dedos e transferindo-o para uma placa rugosa de cartolina. – Ei-lo definitivamente morto. Fácil, não é?”

“ – O facto é que era uma pessoa estranha com interesses esquisitos, com manias absurdas: Olhe, pouco antes de morrer, por exemplo, veio pedir-me que lhe explicasse os pássaros, como se os pássaros, não é, se pudessem explicar: nunca compreendi o que ele queria dizer com aquilo:

os pássaros, oiça lá, você entende?”

“So I offer Liam this picture: my two daughters running on the sandy rim of a stony beach, under a slow, turbulent sky, the shoulders of their coats shrugging behind them. Then I erase it. I close my eyes and roll with the sea’s loud static.

When I open them again, it is to call the girls back to the car”

“ when my grandmother walked in through the door. His baby eyes. His two black pupils, into which the double image of Ada Merriman walked and sat. She was wearing blue, or so I imagine it.

Her blue self settled in the grey folds of his brain, and it stayed there for the rest of his life”

“But this is 1925. A man. A woman. She must know what lies ahead of them now. She knows because she is beautiful. She knows because of all the things that have happened since. She knows because she is my Granny, and when she put her hand on my cheek

I felt the nearness of death and was comforted by it.”

“ I was opening the car door for the girls one day before Liam died and, as it swung past, I saw my reflection in the window. It disappeared, and I looked into the dark cave of the car as the kids came out, or went back in to pick some piece of pink plastic junk off the floor. Then the reflection swung back again, swiftly, as I shut the door. The sun was breaking through high-contrast clouds, the sky in the window pane was a wonderful, thick blue, and in my dark face moving past was the streak of a smile.

And I remember thinking, ‘So, I am happy. That’s nice to know’”

“If you ask me what my brother looked like after he was dead, I can tell you that he looked like Mantegna’s forshortened Christ, in paisley pijamas.

I was glad I had some practice in this whole business – the viewing business – because although I loved Charlie, it was with the easy, anxious love of a child, that is always ready to love someone new.”

“You might call it a crime of the flesh, but the flesh is long fallen away and I am not sure what hurt may linger in the bones”

“ Liam’s mottled purple while Charlie’s was clear, because his body had already forgotten that it was winter, in that cold house. There are photographs. There is the hint of my brother’s smile in my own mirror, a tone of voice I sometimes hit.

I do not think we remember our family in any real sense. We live in them, instead.”

“As I open the fridge, my mind is subject to jolts and lapses; the stair you miss as you fall asleep. I fell the future falling through the roof of my mind and when I look nothing is there. A rope. Something dangling in a bag, that I can not touch.”

“ I wait for the kind of sense that dawn makes, when you have not slept. I stay downstairs while the family breathes above me and I write it down, I lay them out in nice sentences, all my clean, white bones”

“That Christmas morning was as clean and crisp as it always is – my memory will not allow it to rain. But neither will it allow us home.”

“They had a story, Ada and Charlie, in which they each played the most important roles, and when she walked across the room to him, you could tell how fated they felt, as if their love was a great burden to them as well as a joy”

“I do not know why Ada married Charlie when it was Nugent who had her measure. And though you could say that she did not marry Nugent because she did not like him, that is not really enough.

We do not always like the people we love – we do not always have that choice.”